Learning from LLM Experiments

Defining Our ML Data Strategy

LLM Pivot

In 2024, Flatiron Health began seeing diminishing returns from its proprietary deep learning models as public, generally-trained LLMs started to surpass them. Our Machine Learning team began experimenting with open-ended predictions to regain our edge. On the product side, we wanted to understand how best to use LLMs to find and curate data in clinical workflows. These lean experiments—primarily failures—ultimately defined our strategy for the Patient Chart Extractor (PCE) app.

Abstraction at Flatiron

Clinical data is often buried in stacks of PDF visit notes and billing reports. To structure this data (e.g., drug start/end dates), "abstractors"—oncology-trained experts—manually pull information into forms. This process takes 15–85 minutes per task and costs $29 million annually. We explored whether LLMs could speed up or partially replace this expensive workflow.

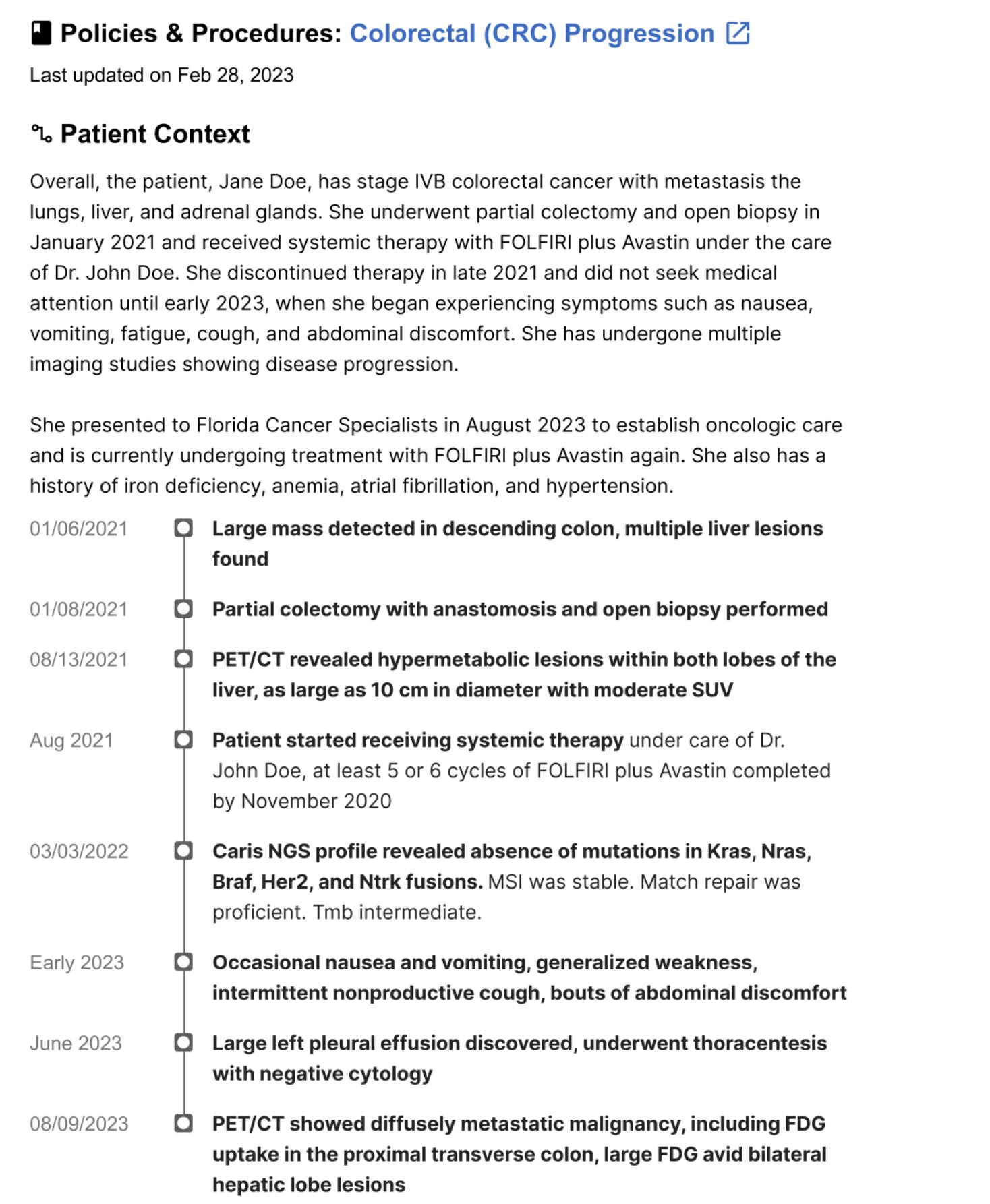

Part 1: Patient Summary Experiments (Q1 2024)

What We Tried:

We prototyped universal patient summaries in Patient Manager to give abstractors a high-level journey overview, assuming it would help them locate specific dates faster.

Outcome:

Feedback was enthusiastic, but summaries were too generic and lengthy. Abstractors working on a specific diagnosis don't need a comprehensive hospitalization history; they found the information interesting but not useful for completing specific tasks.

Key Learnings:

Generic summaries fail because clinical work requires extreme specificity. Abstractors need targeted data (e.g., "Is there evidence of biomarker testing?") rather than broad medical biographies. This shift pushed us toward specialized modules over broad summarization.

Technical constraints were also significant. Oncology charts grow by 40–200 documents annually, and 40–50% of the content is copy-pasted. LLMs would often repeat information, report incorrect years, or exceed context windows and miss crucial data. Finally, we learned that user delight is a dangerous metric for LLMs. LLMs hallucinate with confidence; I had to teach the team to observe behavior, as "I can't believe you can make a summary!" means nothing if users re-read every document anyway.

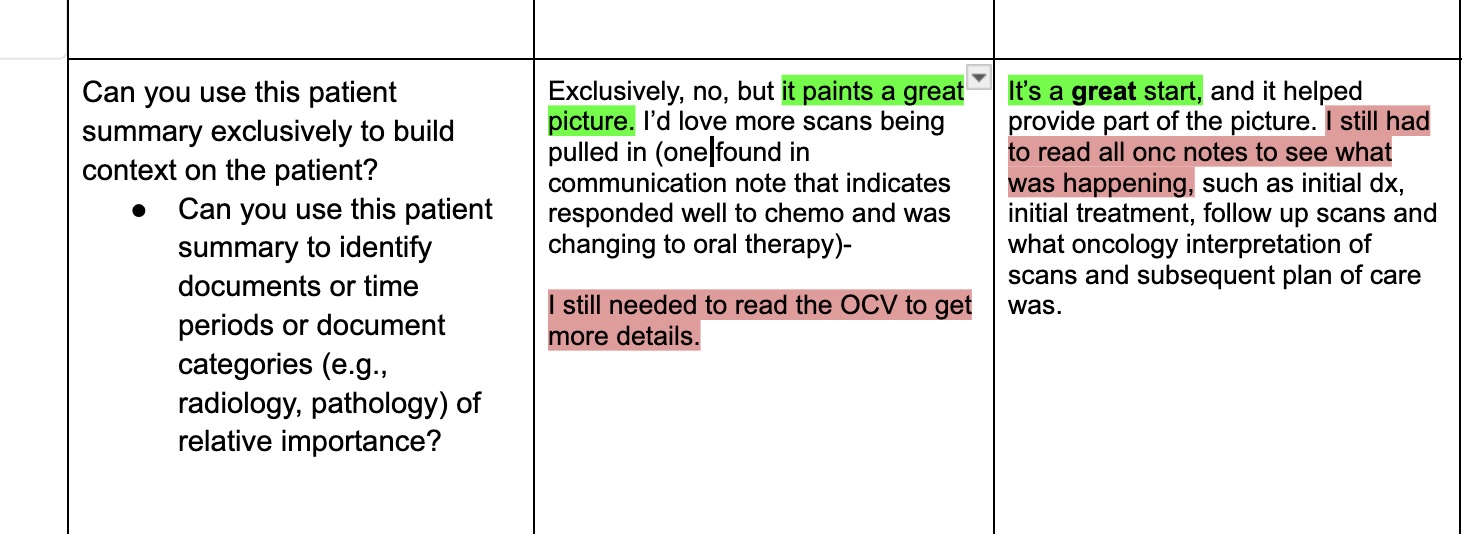

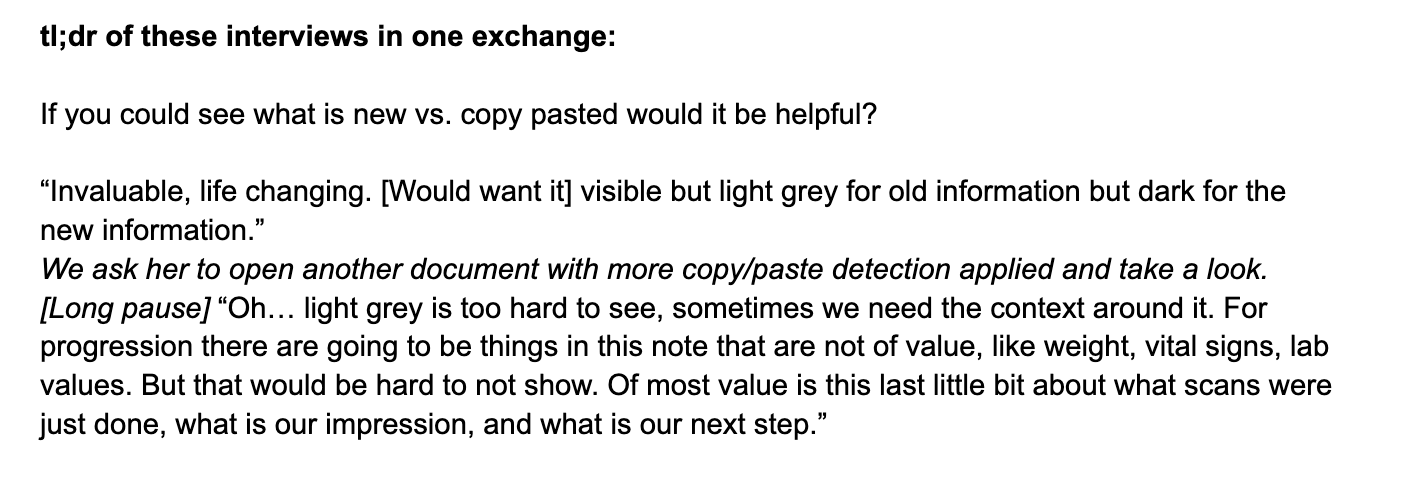

Part 2: Copy Paste Detection (Q3 2024)

What We Tried:

We pivoted to identifying and greying out copy-pasted text to save LLM memory and highlight only net new sentences that didn't exist in previous notes.

Outcome:

Prototypes were a hit; users called the feature "life-changing," and abstractors were 36% faster in live experiments. However, when we released the "git diff-style" implementation, sentiment cratered. Users found the greyed-out text hard to read and were stressed by the missing context. Up to 60% of users disabled the feature, and actual efficiency gains dropped to 15%.

Key Learning:

We realized that injecting radical changes into decade-old workflows creates friction for relatively small gains. This highlighted the need for a fundamental shift in how abstractors interact with data. We also decided to decouple LLM experiments from the main Patient Manager tool to explore value for other internal stakeholders.

Part 3: ML-Derived Data Insertion (Q4 2024)

What We Tried:

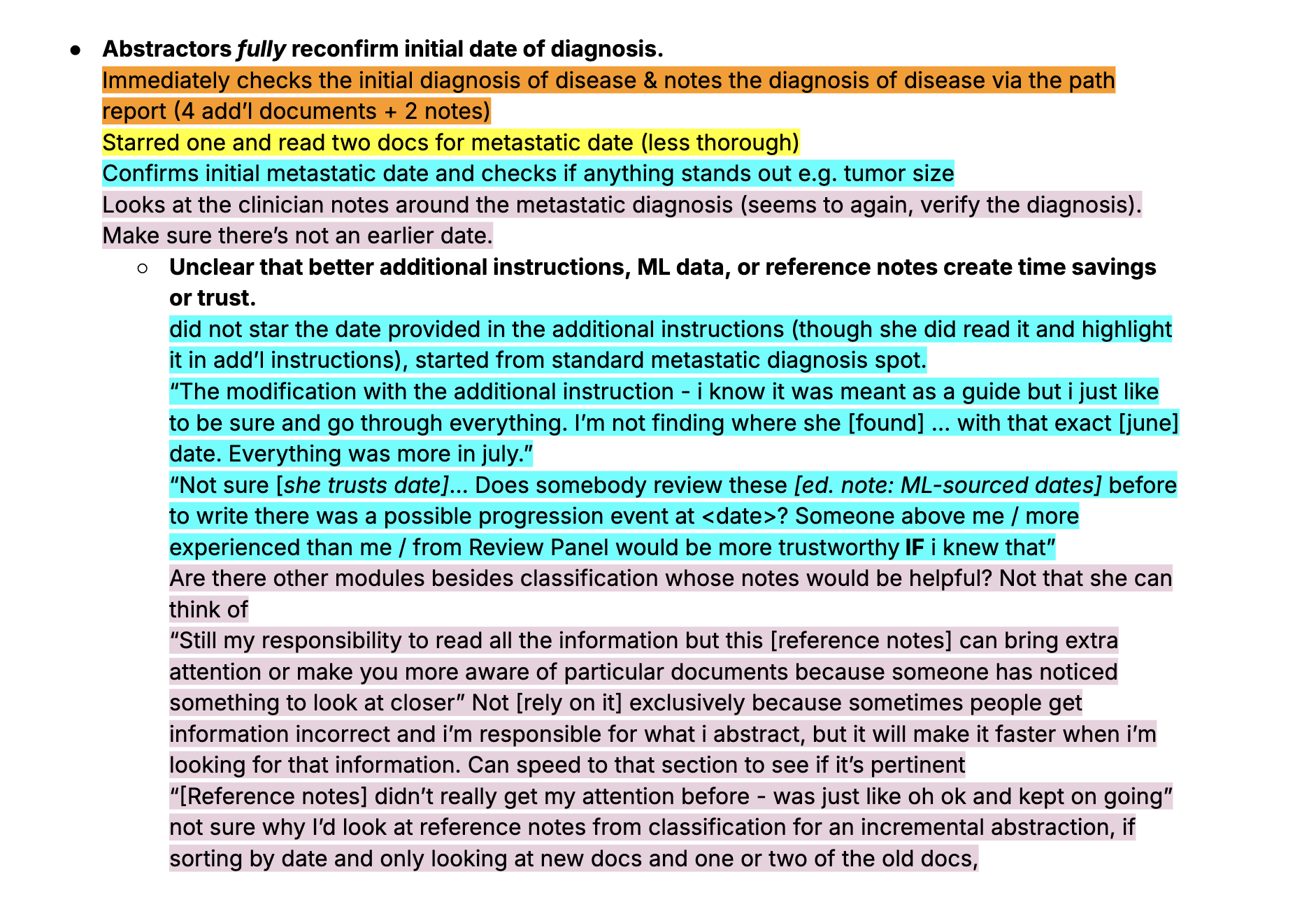

We surfaced ML-predicted biomarker reports or diagnosis dates directly within tasks to give abstractors a "head start." For example: "Patient was diagnosed on dateX and likely first progressed on dateY. If dateY is accurate, continue on to next progression.""

Outcome:

Because predictions lacked context or document references, abstractors had zero trust. They "relitigated the chart," manually verifying earlier diagnosis dates and negating time savings. We pivoted after seeing multiple users immediately return to the beginning of the patient chart, sometimes even earlier than dateX.

Key Learning:

Users won't trust "black box" data without fundamental workflow changes. We realized abstractors were only comfortable with existing data in "incremental" tasks (updating previously abstracted charts). This led to Data Review Tasks, where abstractors review and correct LLM-sourced content rather than finding it from scratch.

Clinical Pivot: Chart Review Service (Q1 2025)

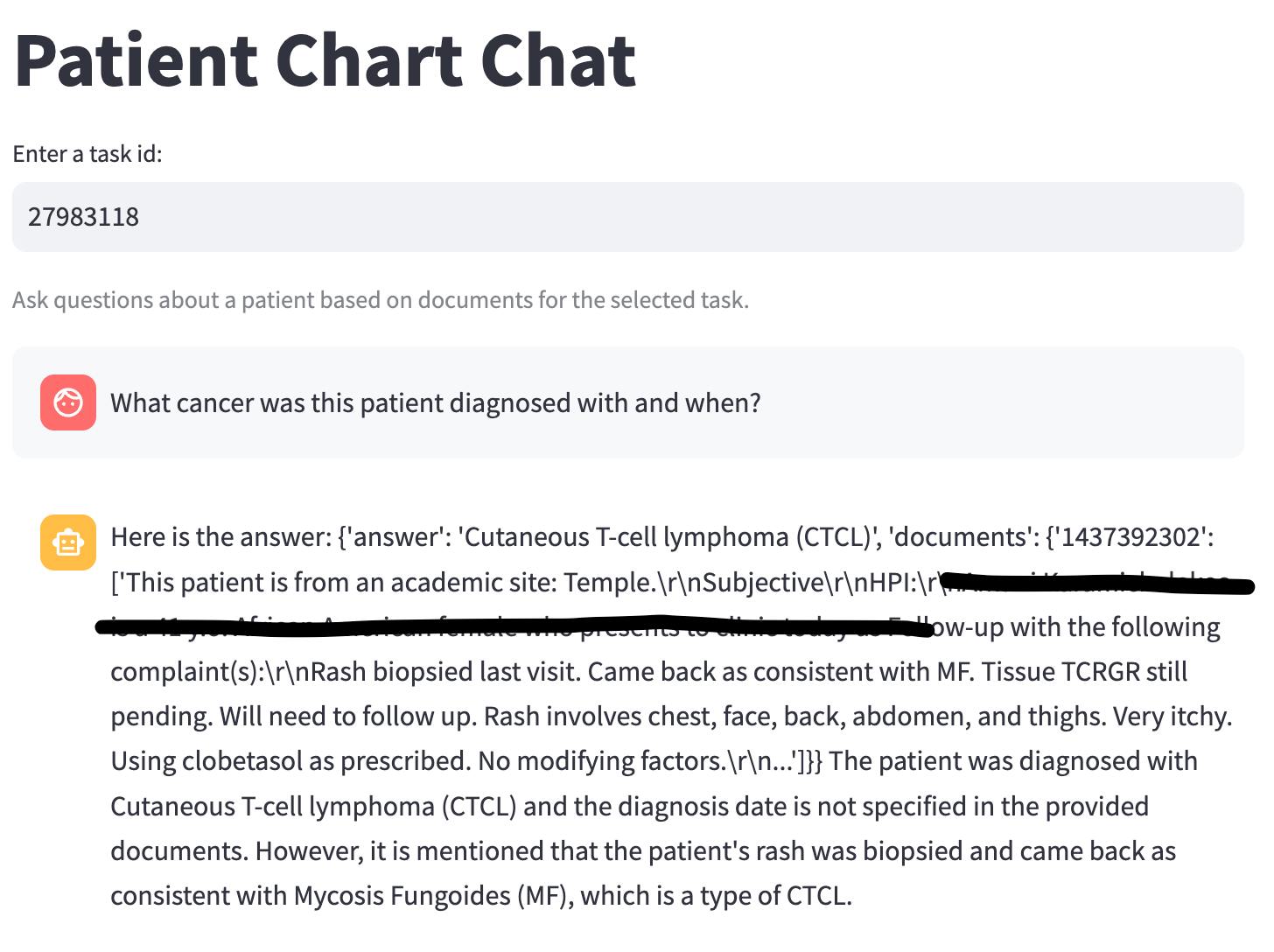

We then engaged Clinical Data (CD) managers, who assess project feasibility. We built a Streamlit chatbot for single-patient queries to test the depth and specificity users required.

Outcome:

CDs found limited value in querying individuals; they needed cohort-level insights and batch operations. However, they confirmed that being able to verify data presence across a cohort (e.g., "3/50 patients have this trial drug") was highly valuable at scale.

What We Learned:

Our ideal user was actually a semi-clinical expert who could come up with complex questions and benefit from "close enough" results across multiple patients. While abstraction is the gold standard for final data delivery, decent AI insight is better than none for scoping deals, QA, and disease exploration.

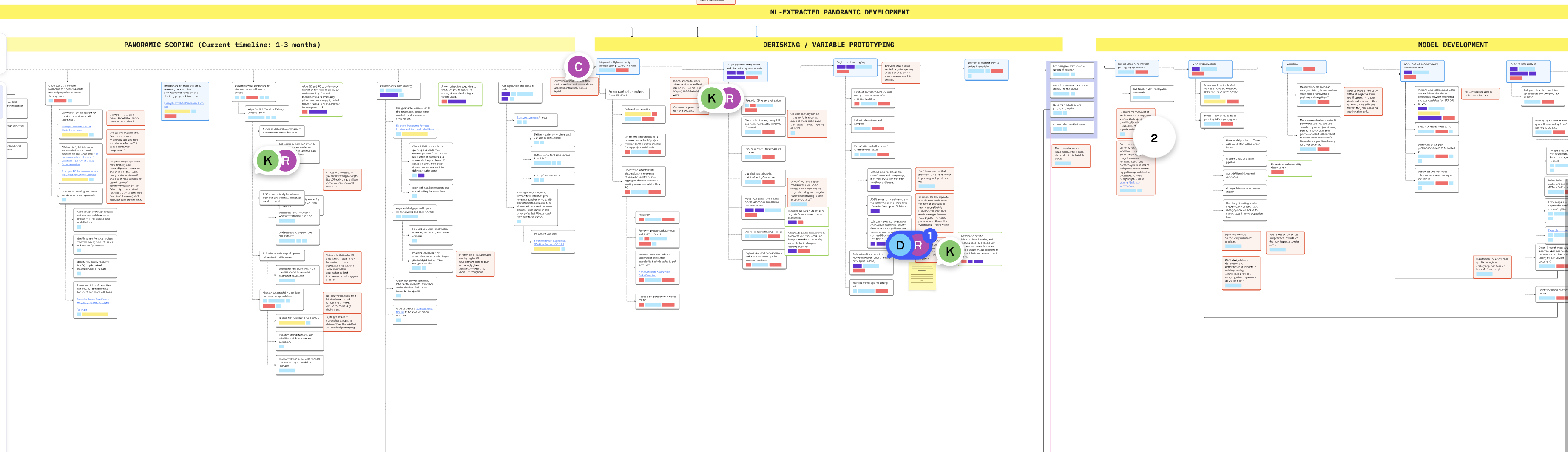

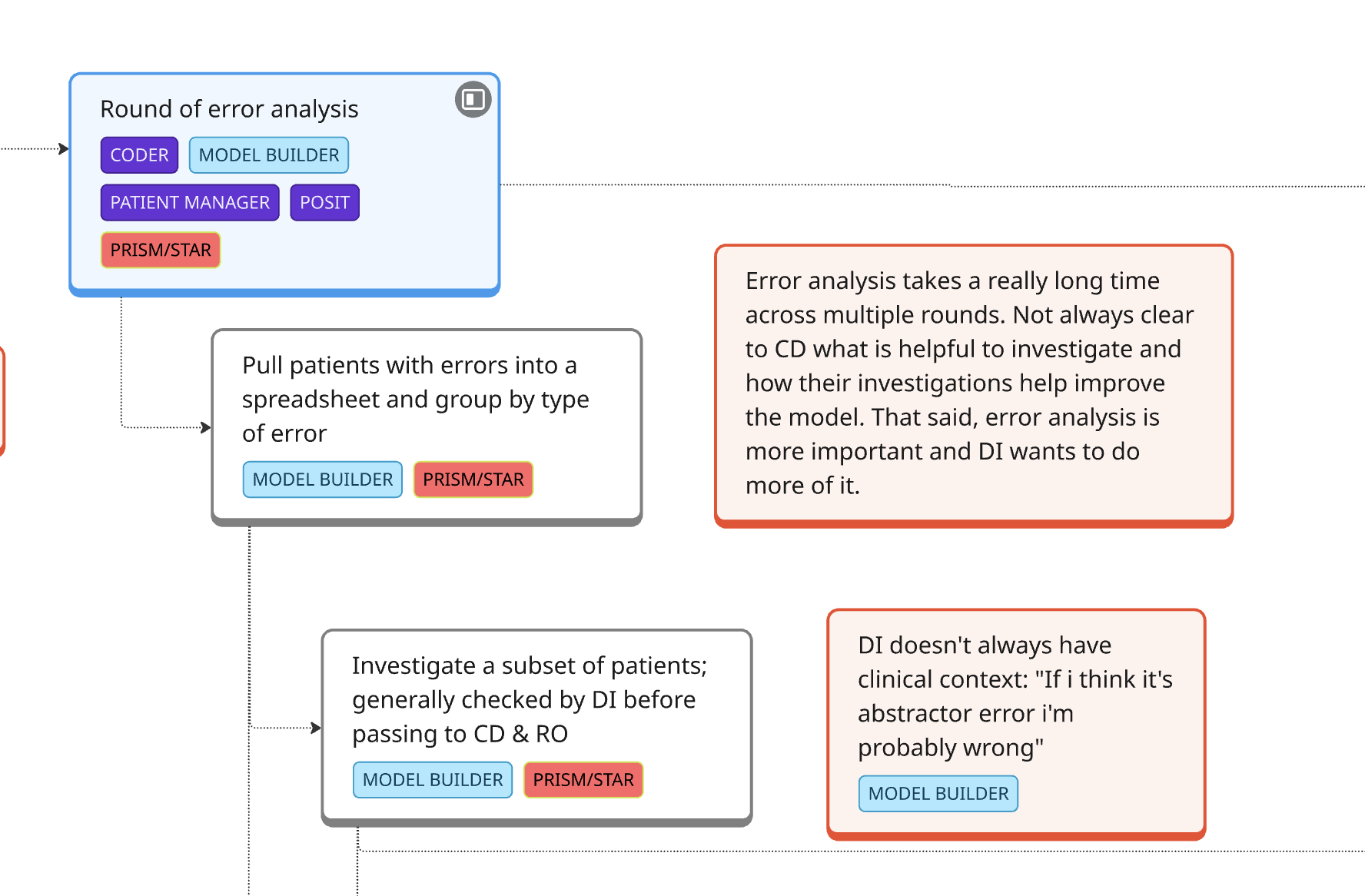

Service Blueprint (Q4 2024)

In parallel, we conducted a contextual inquiry into how Machine Learning Engineers (MLEs) develop LLM models at Flatiron.

Outcome:

We found that MLEs were spending massive amounts of time on clinical work—finding the right cohort data and learning oncology concepts—often poorly. We realized that if clinical users had direct access to run their own LLMs, they could handle the majority of development themselves.

Learning from Failures & Designing for Scale

We built a low-fidelity version of Patient Chart Extractor (PCE) for batch queries. Through this year of testing, we established these core principles:

- Scale over individual depth: PCE provides batch-level insights for entire cohorts.

- Transparency: Every result includes the LLM’s logic and direct references to source documents to build trust. Show users early and often what reasoning and output looks like.

- Targeted over generic: Users must define specific variables and search terms, which improves performance and relevance. Encourage users to engage critically with the chart and refine model inputs.

- Human-in-the-loop: Make PCE as accessible as possible to anyone at Flatiron with some clinical knowledge. Make sure PCE outputs are validated by clinical reviewers and use PCE as a filter leading up to, not a replacement for, abstraction.

PCE is now active across multiple teams. By learning through failure, we built a tool that has generated over $1.5M in new project earnings and created a solid foundation for LLM integration at Flatiron. We are in conversations to bring more technical workflows into PCE and start democratizing what was previously MLE work only.

← Back to work